Thavibu Contemporary Art from Thailand, Vietnam and Myanmar/Burma

Myanmar and East Germany – A Cultural Exchange With Myanmar’s U Lun Gywe

from Art Works by Bui Xuan Phai from the Collection of Van Duong Thanh

By Alice Mann,

Published 03 May, 2013

Cultural exchanges are an important and effective way to familiarize and deepen one’s understanding of a foreign culture and its people firsthand. Cultural exchanges in the art world have enabled artists worldwide to learn and understand their peer’s cultures which has led to a deeper understanding of artworks from other regions. However, travelling is not to be underestimated, considering an artist’s possibility to collect impressions firsthand in a foreign country. With ease of travelling in today’s age, cultural exchanges are on the increase, contrary to some 4 decades ago when political situations posed a barrier.

During the Cold War era, the German Democratic Republic began establishing international relations through art competitions with foreign nations. Burma (present day Myanmar) was a country ruled by a military government from 1962. Despite the resulting economic and social isolation, there was an art scene not only characterized by Burmese tradition but also by an influence of western art.

In the second half of the 20th century Burmese art often combined Buddhist expressions with European techniques or themes, which had its origin from Burma being a former British colony. U Lun Gywe, now considered the living master of Burmese Impressionist painting created works representative of this sort of Western and Burmese traditional style. U Lun Gywe (b. 1930) became one of the most important Burmese artist in his time. His paintings portray a deep emotional connection to his country and Buddhism. He was schooled in European art which can be seen in his paintings. His paintings reflect an interpretation of these studies combined with his own Burmese origin.

Whereas European paintings were characterized by realistic and natural shapes, which are based upon the principles of the Renaissance era, Burmese art reflects spiritual and religious theme. This theme is apparent despite western influences. Such style was primarily enforced by the artist U Ba Nyan (1897-1945) in Burma. U Ba Nyan studied in London by himself and accomplished his style as a teacher at the State School of Fine Arts of Rangoon. He passed the style down to the following generations beneath U Lun Gywe. So, the doctrine of Realism, Naturalism and Impressionism was integrated into the curriculum of art schools in Burma and even resisted the appearance of a new modern trend of art in the 1960’s. The seclusion of Burma from the rest of the world had its effect on the art scene. It was only partially influenced by outer impacts like for example cultural exchange.

U Lun Gywe had two significant residences abroad during his time as the instructor at the State School of Fine Arts in Rangoon (1958-1979). In 1964 he travelled to China and resided for a year for a cultural exchange program. While there he studied traditional brush techniques and oil painting at the Beijing Central Fine Arts Academy. In 1971 he resided for a year in East Germany to study European art and restoration. This would prove to be one of his most significant experiences. During the Cold War era cultural exchanges with East Germany also contained political interests. East Germany needed international acceptance especially to set itself apart from West Germany and they tried to achieve this by developing ties with other countries whom eventually became their allies and adopted the soviet-socialistic model of state. Burma did not have any alliance with the western countries and maintained its neutrality in the Cold War as a member of the Non-Aligned Movement (to 1978). [Reichardt, Achim: Die internationale Solidaritetsarbeit der DDR, in: „offen-siv" 10.10.2009, Verband fur internationale Politik und Volkerrecht e.V. Berlin, www.vip-ev.de/text520.htm].

In practice commercial settlements were built to stabilize the international correlation. In Burma, East Germany was involved in economical, political and development aid. While on the one hand there was material support, on the other hand they established cultural contacts. They arranged delegations of economical and technical specialists to ensure the education of the Burmese locals, whom were also sent to East Germany to receive education especially in the cultural and scientific sector. These training arrangements were always subject to the political interests and resulted from political agreements. As such, teachers and students as well as the curriculum were subjected to East Germany’s political conception. Students went East Germany to complete their professional training through scholarship resulting from the agreements between governments, companies or universities.

In 1971 U Lun Gywe obtained such a scholarship and was sent by the Ministry of Culture of Burma to learn about restoration in East-Germany. Prior to this Professor Ingo Tim from Berlin spent a few months in Yangon. He was working as a restorer of canvases at the National Museum. Among other artist he mentored were U Lun Gywe on the practical skills of restoration technique.

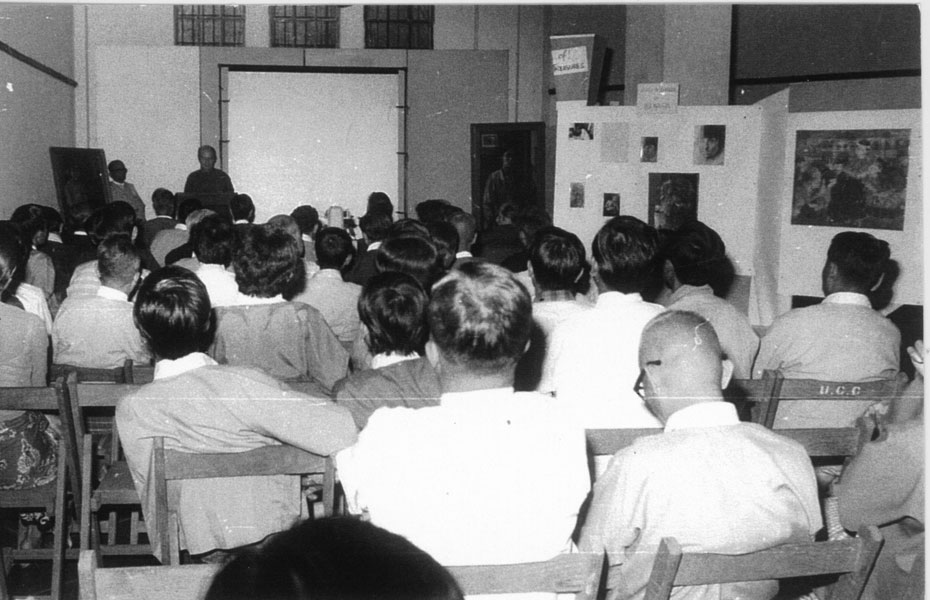

Presentation on the occasion of the exhibition about restorations at the National Museum Rangoon, 1975. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of Myanmar.

Apart from the planned theoretical schedule of discussing the conservation and presentation on the occasion of the exhibition about restorations at the National Museum of Rangoon, 1975 to work on a specific self-portrait of U Ba Nyan. It belonged to the National Museum but it was in poor condition, thereby prompting Professor Timm to restore it immediately. In doing so U Lun Gywe and the chemist, U Ba Tint, proved to be very pro-active and interested. Soon, the restored picture of U Ba Nyan and the appending documentation about the restoration were presented to the museum and the public.

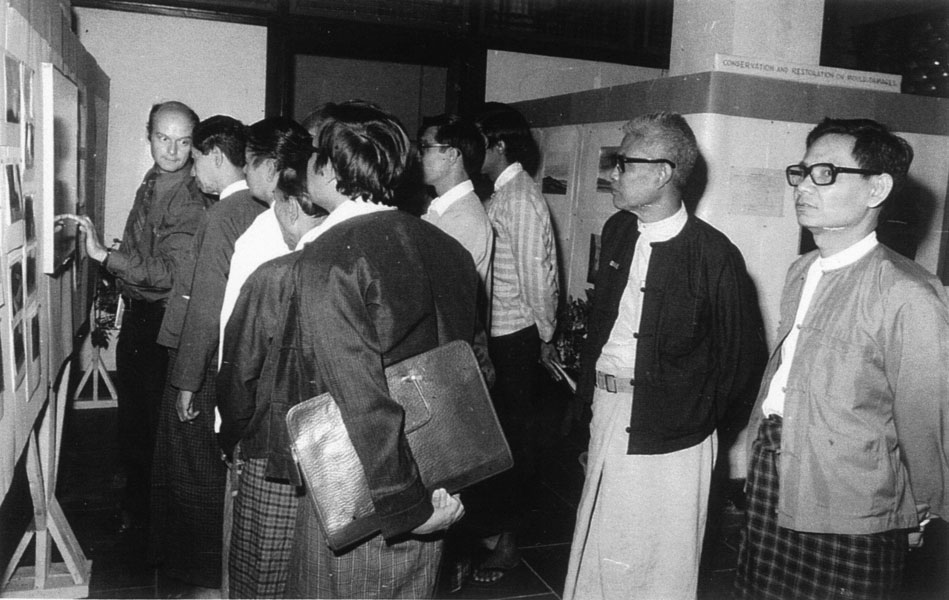

Explanation about a restoration documentation, right: U Lun Gywe. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of Myanmar.

In the course of planning a department for restoration at the National Museum, Professor Ingo Timm recommended U Lun Gywe to the government. He also recommended that U Lun Gywe gain further experience through a cultural exchange with East Germany. U Lun Gywe welcomed the opportunity.

He spent a year in Leipzig, East-Berlin, Potsdam and Dresden. At the beginning of his stay he had to learn German as a preparation for his study. It was mandatory for all foreign students and was conducted at the Herder-Institut of the Karl-Marx Universitet in Leipzig. After this stint he spent half a year at the Markische Museum in Berlin. There he was mentored by the very well-known Professor Timm himself.

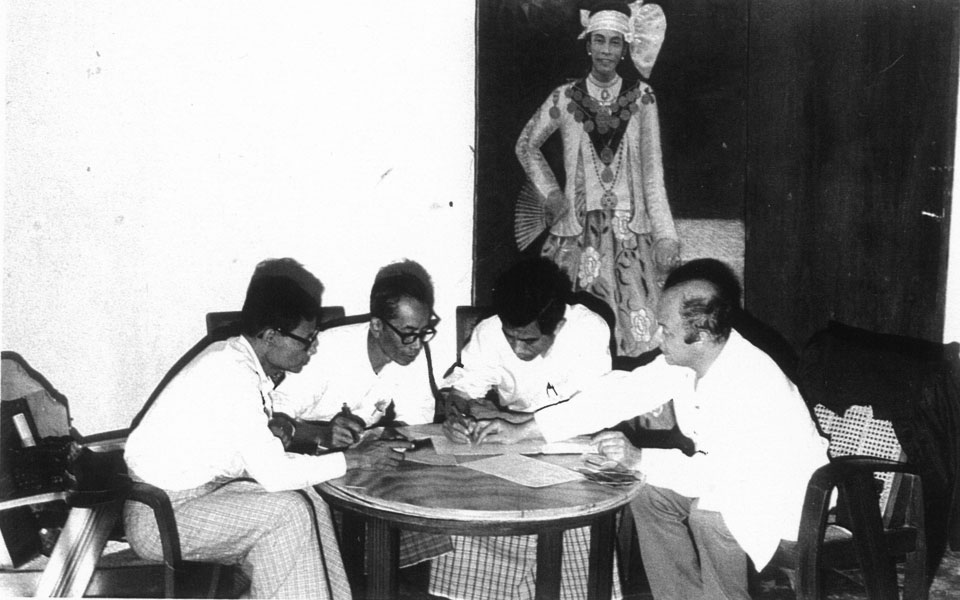

Session at the National Museum Yangon, left: U Lun Gywe, U Ba Tint, U Khin Maunk Phyu (Curator), Ingo Timm, 1975. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of Myanmar.

Next he visited the National Collection of Art in Dresden, where he dealt with the picture gallery. Both museums had an inter-coordinated training program and taught theoretical, as well as, practical skills of restoration. U Lun Gywe wrote down all learned working methods in a notebook. Furthermore he drew all used tools and equipment. Finally they did not institute a restoration workshop at the National Museum in Rangoon. However, U Lun Gywe engaged in further restorations of U Ba Nyan’s paintings. Aside from all this useful education, unfortunately there is a negative aspect of such cultural exchange, because of the political calculations and gains involved. The entire exchange program of East Germany did seem to be geared to forming future supporters of socialism and to spreading socialism modeled from Moscow or East Berlin.

A cultural exchange is a person’s unique personal experience. Ultimately for U Lun Gywe, it was the meeting of different cultures and the buildup of longtime friendships. For his career as an artist he gained important experiences and skills: he learned conservation techniques; he saw and studied European art with his own eyes in the museums from which he eventually carved out his own impressionist style with an expressionist paintbrush technique and traditional Burmese content.